Researching mythology is something that I enjoy, trying to find accurate information so that my writing can better depict mythological figures. One deity that I’ve been looking into for some time now is Tezcatlipoca, a major Mexica/Aztec1 god. As a result of that research I’ve found myself completely turned off by how most works of fiction demonize him.

I’d like to do my part in sharing what I know to help clear the record about Tezcatlipoca. Before that however, I want you, the reader, to keep in mind that I’m not an expert myself. I will however mention several sources I’ve used at the end of this post.

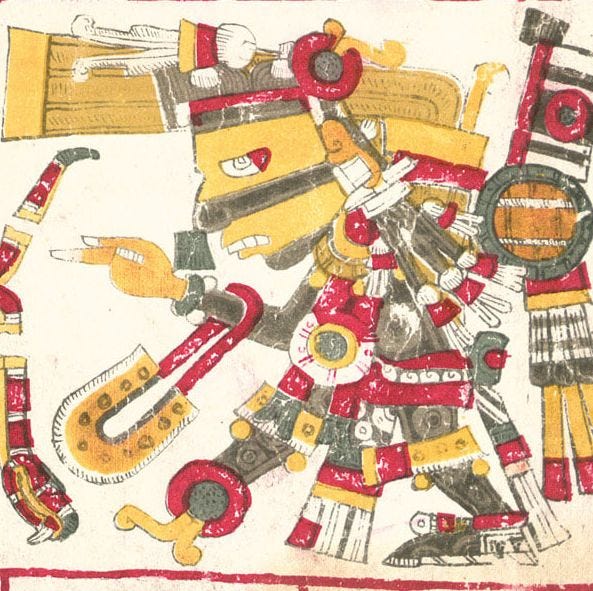

To start, Tezcatlipoca has several identifying features in art, such as a horizontal black band across his face. Obsidian mirrors in general are a symbol of Tezcatlipoca, whose name even means ‘smoking mirror.’ Some pieces of art even give him a mirror as a foot in reference to one story.

Of Tezcatlipoca’s various animal associations the jaguar is the most prominent. But he has connections to other animals including the horned owl, coyote, and turkey.

Another identifying symbol of his is the ezpitzal. The ezpitzal is a heart within multiple streams of blood that end in stones. It’s considered to be a symbol of anger, since the verb ‘pitzal’ can refer to expressing anger.

In the picture above you can see the ezpitzal on the head of Tepeyollotl, the figure on the left and an aspect of Tezcatlipoca. If you have trouble finding it, it looks a bit like a red hand with green dots on the end to me. Remember that the Mexica didn’t draw hearts the way we do. Standing opposite to Tepeyollotl-Tezcatlipoca is Quetzalcoatl.

Mexica culture appears to have far less interest in trios than what many have come to expect. Instead it is more concerned with duos and quartets. Tezcatlipoca forms a duo with his twin Quetzalcoatl, and they are part of a quartet with Huitzilopochtli and Xipe Totec as a group of brothers2. Sometimes all four of them are called Tezcatlipoca.

The four Tezcatlipoca are distinguished by a color in their name. Tezcatlipoca becomes Black Tezcatlipoca, White Tezcatlipoca is Quetzalcoatl, Blue Tezcatlipoca is Huitzilopochtli, and Red Tezcatlipoca is Xipe Totec. Each is associated with a cardinal direction, in (Black) Tezcatlipoca’s case the north.3

Tezcatlipoca also has a connection to another quartet, his four wives: Xochiquetzal, Atlatonan, Huixtochihuatl, and Xilonen. Some of these goddesses are notable in their own right, while Atlatonan has been difficult for me to find solid information on beyond being one of Tezcatlipoca’s wives.

Smoking Mirror and Feathered Serpent (and other dynamics)

Out of all the other deities he is connected to, Tezcatlipoca’s most complicated and significant relationship is with his brother Quetzalcoatl. To call them enemies would be oversimplifying, despite what attempts by modern fiction to shove them into some sort of Abel and Cain dynamic would have you believe.

Even academic sources have commented on how flawed the popular understanding of Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca’s relationship is.

“Quetzalcoatl’s and Tezcatlipoca’s respective attitudes regarding human sacrifice have also been used to place these deities in strong opposition: the “peace-loving” Quetzalcoatl facing the “bloodthirsty” Tezcatlipoca. But this caricature does not hold up well under a careful scrutiny of sources.” (Olivier 77-78)

To properly understand Tezcatlipoca, you need to throw out all the nonsense that has been attached to Quetzalcoatl. Quetzalcoatl is not Jesus, Hercules4, a nordic sailor, or an alien. He received human sacrifices like any other Mexica god, because it was a key part of the religion. It’s telling that the most popular Mexica god is often separated from actual Mexica culture as much as possible.

As a duo the two gods are equals, both were revered and respected. They are like fire and water, both are vital, yet you need to be careful when combining them. Boiling water has its own way of causing damage if you’re careless. But it’d better to look at the mythology itself for examples of their relationship.

In many versions of the Mexica creation myth, it is the feuding between Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca that destroys at least some of the four prior worlds. Not everything from those worlds was destroyed, as things like monkeys, fish, and birds are the people of those worlds.

After the first four worlds are destroyed, Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca then work together to create the fifth world by slaying a monster5 and turning it into the earth we walk on today. Tezcatlipoca lost his foot in the process either as part of the fight or due to using it as bait for the monster.

“Thus the cooperation, but above all the differences and oppositions between these two incomplete twins, Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, serve as the true mythical engine that powers the various processes of creation in a universe in perpetual motion.” (Olivier 80)

When it comes to Huitzilopochtli and Xipe Totec, the relationship between them and Tezcatlipoca appears to be defined more by iconography and politics than myth. This makes it harder for me to talk about them, and there isn’t a need to correct a popularized false image of their relationship to Tezcatlipoca, so this is the most I’ll write of them here.

Of Tezcatlipoca’s four wives, Xochiquetzal has the most intriguing relationship to Tezcatlipoca. In some versions of the creation myth her first husband was Tlaloc, then she got with Tezcatlipoca, which led to Tlaloc destroying the world he was the sun of.

Another story has Tezcatlipoca kidnap Xochiquetzal, eventually returning her to Tlaloc. Ultimately she appeared in festivals as Tezcatlipoca’s wife, while Tlaloc was only accompanied in festivals by his second wife.6

Toxcatl and other traditions

The ‘month7’ of Toxcatl featured a major festival that starred Tezcatlipoca. A captive warrior was chosen as his ixiptla, an impersonator or embodiment. There was a strict list of requirements that someone had to meet to become Tezcatlipoca. His ixiptla would be wed to the four ixiptla of his wives.

At one point in Toxcatl, Tezcatlipoca’s ixiptla ascended a temple, breaking a flute on each step. At the top he was sacrificed to himself. Then the next ixiptla for Tezcatlipoca was selected, who wore the skin of the last as a cloak. The flesh of Tezcatlipoca was also eaten during the festivities.

The Mexica sacred calendar assigns each day a number and daysign, which are associated with different deities. Days with the sign reed (acatl) and the number ten (mahtlactli) are connected to Tezcatlipoca.

While there are twenty day signs, the numerical count only goes in cycles of thirteen8. These thirteen day cycles are identified by the day that begins them, which also inform the significance of the rest of the cycle. Tezcatlipoca is associated with the cycles that begin on One-Jaguar (Ce Ocelotl) and One-Death (Ce Miquiztli).

One-Death (also written as 1 Death) itself is notable because it demonstrates another often overlooked aspect of Tezcatlipoca, the protector of slaves. On that day the slaves, Tezcatlipoca’s “beloved sons” were treated with high honors in a reversal of the usual social order. Mistreatment of a slave during this time was punishable by death.

Moving up the totem pole, Tezcatlipoca was patron of the telpochalli, the school for commoners. No matter what status someone had, Tezcatlipoca remained present. That is what first got me interested in him, a god who is associated with royalty, yet is also known as a patron and protector for the lower classes.

A History of Demonization

At the start of this post I mentioned my frustration with how Tezcatlipoca is often demonized by modern fiction, and as you’d expect this can be traced back to colonialism. It was the Franciscan Friar Sahagún who compared Tezcatlipoca to Lucifer.9

There’s also a slight chance you’ve seen or know of a mirror connected to Tezcatlipoca without realizing it, the scrying glass of the magician John Dee, which he used to commune with angels and demons. Analysis has confirmed the Mexica origins of that appropriated artifact.

Lastly, a certain historical event helps give any demonized depiction of Tezcatlipoca a horrid taste for me. The Toxcatl Massacre was a pivotal moment in the Spanish conquest where the Toxcatl festival was disrupted by the Spainards killing everyone.

Portraying a god at the center of the Toxcatl celebrations as evil strays dangerously close to conquistador apologism. Calling Tezcatlipoca evil comes with implicit implications about his worship, the kind that help justify massacring worshippers.

Interesting how the most commonly demonized Mexica god is also among the most convenient to demonize for conquistador friendly narratives.

Conclusion

Tezcatlipoca is so multifaceted that there are many other things I didn’t touch on, but this is only supposed to be a basic introduction. For example I didn’t delve into the archeological findings on Tezcatlipoca or his various names.

Tezcatlipoca is not evil, he’s fearsome. He is a god who pushes people towards ruin or success, one who delivers merciless punishment. He’s also a protector of slaves, patron of the school for commoners, and a symbol of justice.

Sources + Things to check out for yourself

The section of Mexicolore covering the Aztecs/Mexica has been an invaluable asset for this piece. Some particularly useful articles for me are the ones on Tezcatlipoca himself and One-Death.

Aztec Calendar.com helped with looking up info on the sacred day count. I also enjoyed converting my own birthdate into the sacred day count.

The book “Tezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme Deity” was another great resource, though at times too academic for me to easily comprehend.

Not a source, but I wanted to highlight nosuku-k on DeviantArt and their delightful art based on Mexica Mythology, such as this drawing of Tezcatlipoca and his wives. It’s the kind of depiction I wish there was more of.

Citation

Olivier, Guihem. 2015 “Enemy Brothers Or Divine Twins.” In Tezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme Deity, ed. Elizabeth Baquedano, trans. Michel Besson. Colorado: University Press of Colorado

The term Mexica would be more accurate here, as it’s what the Aztecs called themselves. So it’s what I shall use in this article, though the term Aztec does have its uses.

Tezcatlipoca is not always the brother of Xipe Totec and Huitzilopochtli, and sometimes Tlaloc is his brother. Family relationships aren’t always concrete in mythology. Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl’s status as brothers does appear to be consistent however.

Quetzalcoatl is associated with the west, Xipe Totec with the east, and Huitzilopochtli with south.

This comparison was made by Sahagún, who to be fair didn’t mean it literally. I still find it bizarre.

Sometimes the monster is Cipactli, other times it is Tlatecuhtli. There are differences between them in the religion as a whole, despite how interchangeable they can come off as when you look at different versions of the creation myth.

I think I once saw something that placed Xochiquetzal at Tlaloc’s festival, but I couldn’t find it again, the error there might be with my memory.

To my knowledge there isn’t a proper nahuatl word for this type of twenty day period. It does refer to a specific length on the calendar, but our only word for it is a Spanish word, veintena.

Thirteen isn’t unlucky to the Aztecs, in fact it’s a number with meanings of completeness.

Sahagún also compared Tezcatlipoca to Jupiter. Neither comparison hits the mark.