A Non-Gamer's Primer for Battles Beneath the Stars

A bonus for those who need it

Battles Beneath the Stars may be a written work, but it’s one steeped in gaming terminology and conventions. Because of that I hope to make the story more accessible by explaining them. Naturally anyone already familiar with video games can skip this entirely.

To help demonstrate these concepts I’ll be making use of various pictures and screenshots, all of which have been taken by myself.

Defining the genre

Fighting games are a video game genre that is most often about one on one combat, the genre defining game being Street Fighter II. At its core the gameplay is about two characters fighting each other with the goal of reducing the other’s lifebar to zero.

Battles Beneath the Stars borrows a lot from the platform fighter subgenre specifically, which is what Super Smash Bros fits into. Platform fighters have a greater focus on movement and simpler controls, and define victory by sending opposing players out of the arena.

Part of my vision for Battles Beneath the Stars as a game is being in between categories, with both lifebars and knock out as win conditions. The game closest to it would be Super Smash Bros when set to its stamina mode, rather than the default game modes. So look below for a screenshot from Super Smash Bros Ultimate set to stamina mode.

In traditional fighting games there is rarely any meaningful distinction between the stages that combat takes place on. Battles Beneath the Stars goes with the platform fighter approach however, where stages have unique layouts and hazards that impact the outcome of fights.

With their sizable rosters of distinct characters, fighting games are inherently ensemble pieces. The early arcade games were light on story, but with what story there was the main character became whoever you wanted to play as on the roster. Battles Beneath the Stars draws on the ensemble nature of fighting games, letting multiple characters have a go at being the main character.

Defining formatting

Dialogue in Battles Beneath the Stars is written in script format. However, rather than trying to be like a film script, it’s trying to convey the use of text boxes, one of the classic methods for video games to display dialogue.

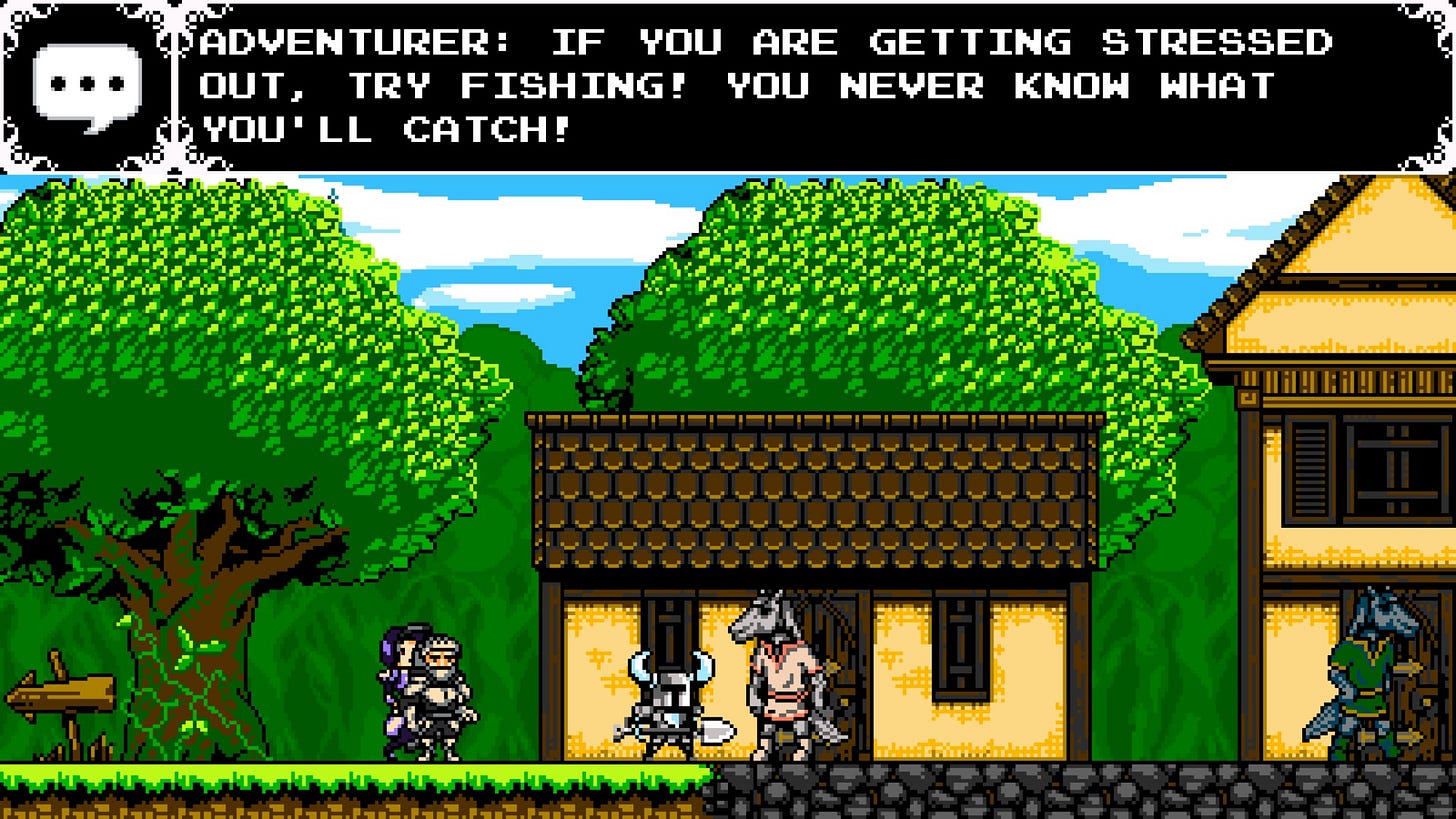

Sometimes while exploring in a game you can talk to or listen in on minor characters, something Battles Beneath the Stars tries to incorporate with its exploration sections by having dialogue to eavesdrop on. The example above comes from Shovel Knight: Shovel of Hope.

Some games pair text boxes with artwork of the characters, which have multiple versions to show different expressions and help make dialogue feel more dynamic. The game shown above is Melty Blood: Type Lumina.

When a character is listed as speaking twice, that usually means the dialogue is across multiple text boxes. Though I tried to think more about the pacing of lines rather than imagining actual text box constraints. In a real game sometimes sentences get cut across multiple text boxes, which doesn’t look good there and would look even less elegant in this format.

For games that don’t have voice acting, it’s also common to have text scrolling sound effects, with some games having several to function as ‘voices’ for characters. So dialogue in Battles Beneath the Stars could be imagined either voiced or with those kinds of sound effects, and both would fit the video game framing equally well.

The way the exploration sections and fights are written is modeled like a walkthrough for a video game. I have some fondness for the physical guidebooks for games I used to get at game stores, and for when I used to regularly consult GameFAQS for walkthroughs while playing a game.

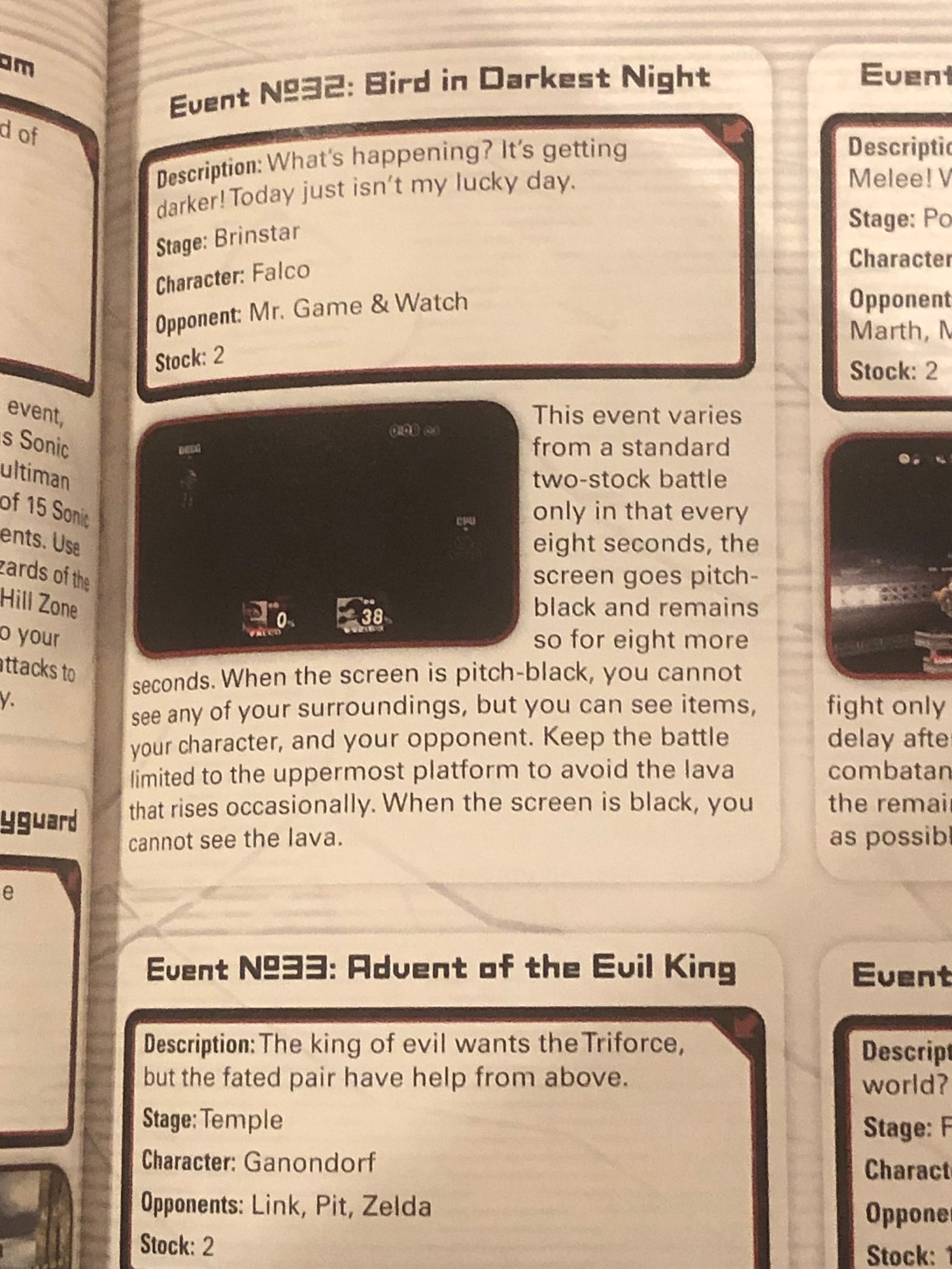

Below are some pictures from a guidebook for Super Smash Bros Brawl, showing both exploration and combat.

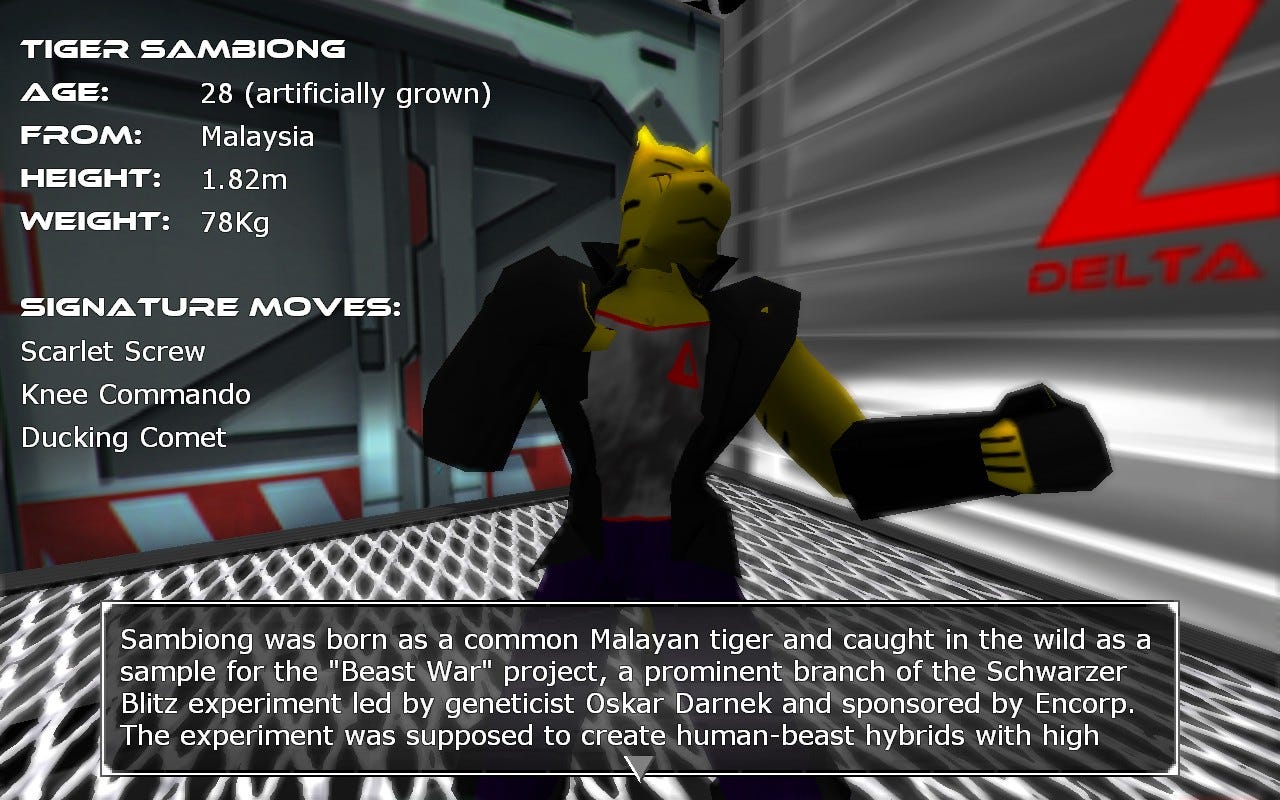

The profiles for Battles Beneath the Stars are also inspired by a common feature in fighting games where they include profiles detailing the backstory of each character and other information. Included below is one such example from Schwarzerblitz.

Defining terminology

Naturally when describing how to win a fight in a fighting game, you have to employ some of the genre terminology. Thankfully there is an online glossary of fighting game terms, but I’d like to offer my own explanations, since telling you to look it up elsewhere is against the spirit of this entire post.

Generally there are three types of attacks in fighting games, normal moves, special moves, and super moves. Normals are called that because they’re executed by simple inputs like a single button press or a button press with a certain direction pushed in on the control stick.

Special moves are a character’s signature attacks that often involve more complex inputs, such as Ryu’s genre defining hadouken and shoryuken attacks, which are so iconic even the inputs to use them are common knowledge for gamers.

Super moves are usually a character’s strongest and flashiest attacks. These are often linked to a meter that needs to be filled to a certain extent before using it, upon which it will consume that meter and need to be built up again. Most games will have other uses for that meter as well, but I couldn’t get too intricate on the imaginary game aspect of Battles Beneath the Stars.

For the screenshot above, look at the purple bar on the left side of the screen with a 3 next to it.

Now that a super move has been used, look at that bar again. Notice how part of it is empty and the number has changed to a 2, which signifies it still has enough for two more super moves. The game shown in these pictures is Merfight: Curse of the Arctic Prince, incidentally a game I’m helping edit the story for.

Most fighting games have a sort of rocks-papers-scissors system in place where attacks can be blocked, grabs (coded as a distinct action) can’t be blocked, and attacks stop grabs. What’s also key is that many attacks will leave the user vulnerable if it’s blocked or fails to connect, attacking someone during that period is a punish.

Elements like that have a universal or near universal presence in fighting games, and so invoking them in Battles Beneath the Stars helps sell the feeling of guiding someone through a fighting game. More specific terminology will be explained as it comes up to hopefully avoid overwhelming readers here.

Defining archetypes

There are also a variety of archetypes for fighting game characters to play with, knowing them can help better envision the game side of Battles Beneath the Stars.

Shoto refers to characters focused on the fundamentals of the game, who are decent at all parts of it.

Rushdown characters favor aggressive play with quick short range attacks that require them to always be up close to the opponent.

Zoners refer to characters with long range attacks who focus more on keeping the opponent at a distance.

Grapplers focus on grabs, and will often have a range of different ones to use. A command grab refers to any grab attack beyond the standard ones every character uses, which are most often found on grapplers.

A puppet master is a character who relies on commanding another character through different moves, relying on careful coordination. They’re not as common as other fighting game archetypes.

This should cover all of the game terminology that might be confusing. Although, if my explanations missed something that still leaves you confused, it’d be best if I know so I could correct that oversight.

also: the terms for the archetypes are so fun - choosing to interpret them in a myers-brigg type indicator way. I definitely see myself as a grappler

this very thorough primer left me with one burning question: why is it that Ciel (a female catholic priest) from Melty Blood: Type Lumina refers to herself as a dog when she has no apparent dog features?? 🤔